Ben Wellington lectures applied statistics at the Pratt Institute, without using a text book or aid of any kind; he also quantifies the city of New York. His classroom calculations are based on open municipal data. His blog I Quant NY has attracted media attention as it reveals abnormalities, interesting facts and even bad practices in local public management. His source of information is data from the local agencies themselves.

Small ideas

Wellington is crazy about correlations. In his spare time he has mapped city areas with no public Wi-Fi coverage, revealed which fast food locations are less salubrious and hygienic, discovered that half of New Yorkers live less than four blocks away from a Starbucks, and identified a location were parking signage was very poor. In this last case, he found out that fines in that exact spot were generating abnormally high revenue.

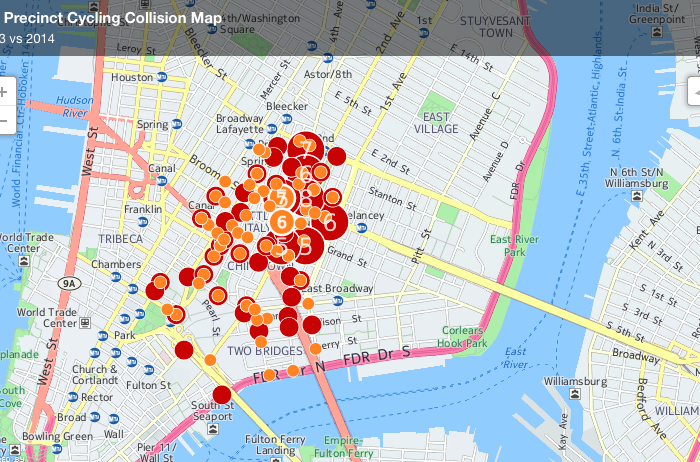

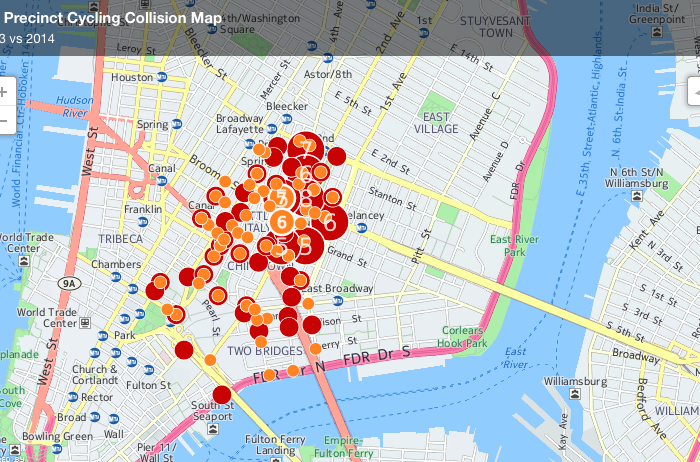

Image: accidents and fines involving cyclists. Source: iquantny

“Open data plays two roles. You’re leveraging the power of people who are passionate to find things. On the other hand, it’s also a bit of a watchdog with transparency and accountability”, Wellington explains. “I want to dig up as many interesting tidbits as possible and put them out there. I let the experts dig in. I don’t know much about traffic safety, but I can analyze the most dangerous places, give that to people who actually know about it, and let them go with it. I’m not going to sit there and make infrastructural suggestions.”

Some agencies are interested in Wellington’s method and findings. He has had “preliminary conversations”, but he is moderately skeptical: “Agencies are not quite sure what to do with this citizen-style, open data”, he states. “When you go to somebody and tell them that something is broken, their first instinct is to get defensive.”

Big ideas

“If we’re going to continue leading the country in innovation and transparency, we’re going to have to make sure that all New Yorkers have access to the data that drives our city…catalyzing the creativity, intellect, and enterprising spirit of computer programmers to build tools that help us all improve our lives.” These were the words of Mayor Michael Bloomberg when he invited eight million New Yorkers to take part in the first NYC BigApps Challenge. This local initiative aims to improve the city’s services and quality of life by using technology and open data.

Bloomberg created an information, data and financial software giant. As a technology entrepreneur, he guided the city in major steps toward promoting technology. During his term, in 2012 the New York City Council approved legislation requiring that all local agencies opened their information until 2018.

BigApps was initiated during Bloomberg’s term in office, is led by the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC). However, people’s enthusiasm for the first editions of this competition did not match the applications’ fate in terms of quality (e.g. Sportaneous, which allows you to organize pickup games of any sports and invite others to join you), number of users (e.g. Roadify, which did not reach a critical number) and success as a business. This was mostly due to the projects’ continuity, particularly their commercial continuity and their successful transformation into start-ups.

The organizers realized that the key was to identify real problems and social challenges, and gather a group of mentors and collaborators who had the knowledge and were interested in finding and sponsoring a solution. In 2014, with Mayor De Blasio at the helm, the competition provided the whole record of vehicle collisions as open data; this dataset had been long sought after by the local community due to this critical importance. And there was also BigIdeas, which allowed organizations, companies and experts in the environment, economy, education and health to sponsor solutions to major local challenges. More than 80 mentors from the technology ecosystem, government agencies and departments, and social organizations provided data, resources and awards (awarding innovation works) for solving important challenges. While these were clear challenges, they were open to the participants’ creativity.

The city opened more than 1,100 datasets and dozens of APIs, systems and devices from private partners to the public. After four months, there were projects such as HealthyOut by Wendy Nguyen, the winning application in the health life category of BigIssues. This easy-to-use solution aims to find healthy restaurant options anywhere in the city. The application has been a success in terms of downloads, and is already available in more than 500 cities.

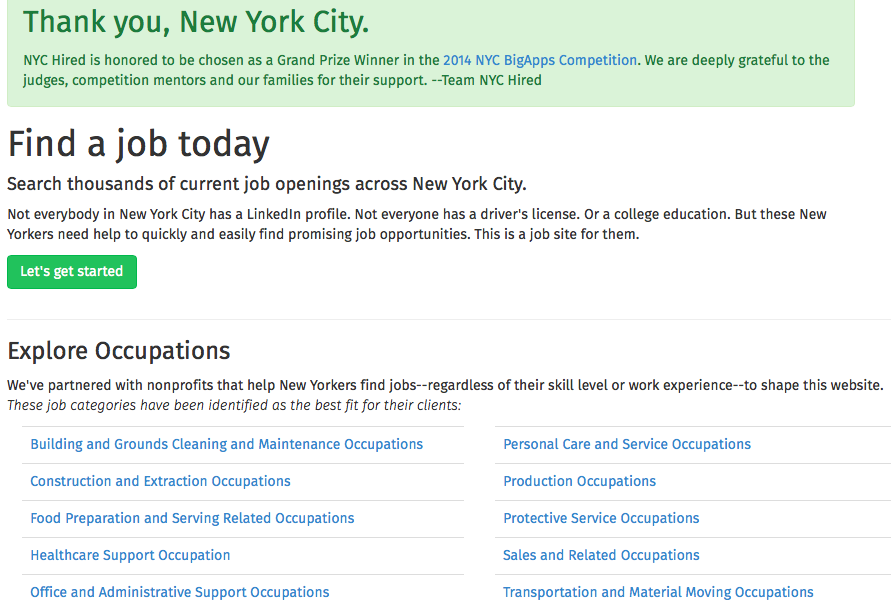

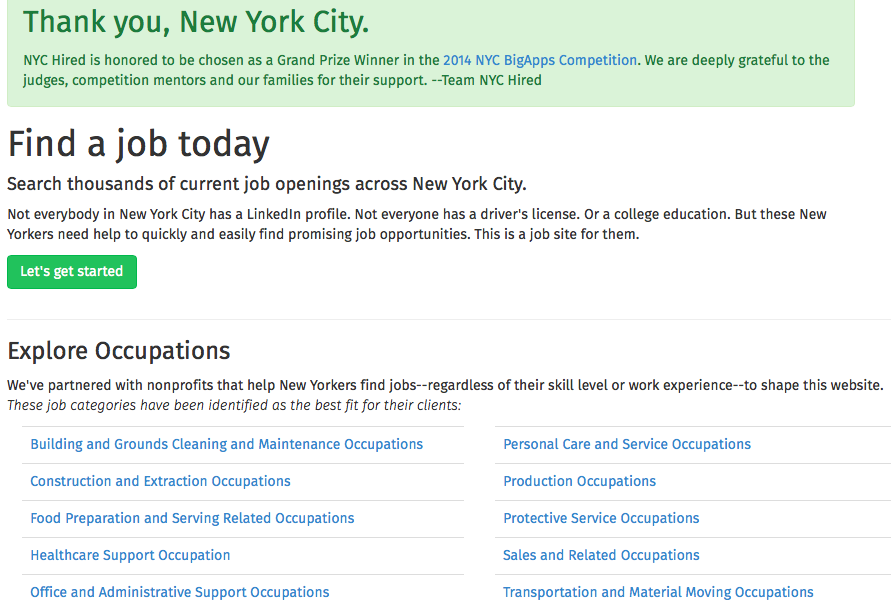

You can check the winners of Big APPS NYC 2014 here. The mentors suggested challenges such as showing the city’s water supply and treatment system in a transparent manner, creating a tool to find out the distribution and demand of power consumption, and even obtaining real-time data about job vacancies and demands for the same day. This last project is called NYC Hired, and its promoters are already working with the NOGs behind the challenge to find work opportunities for New Yorkers in real time.

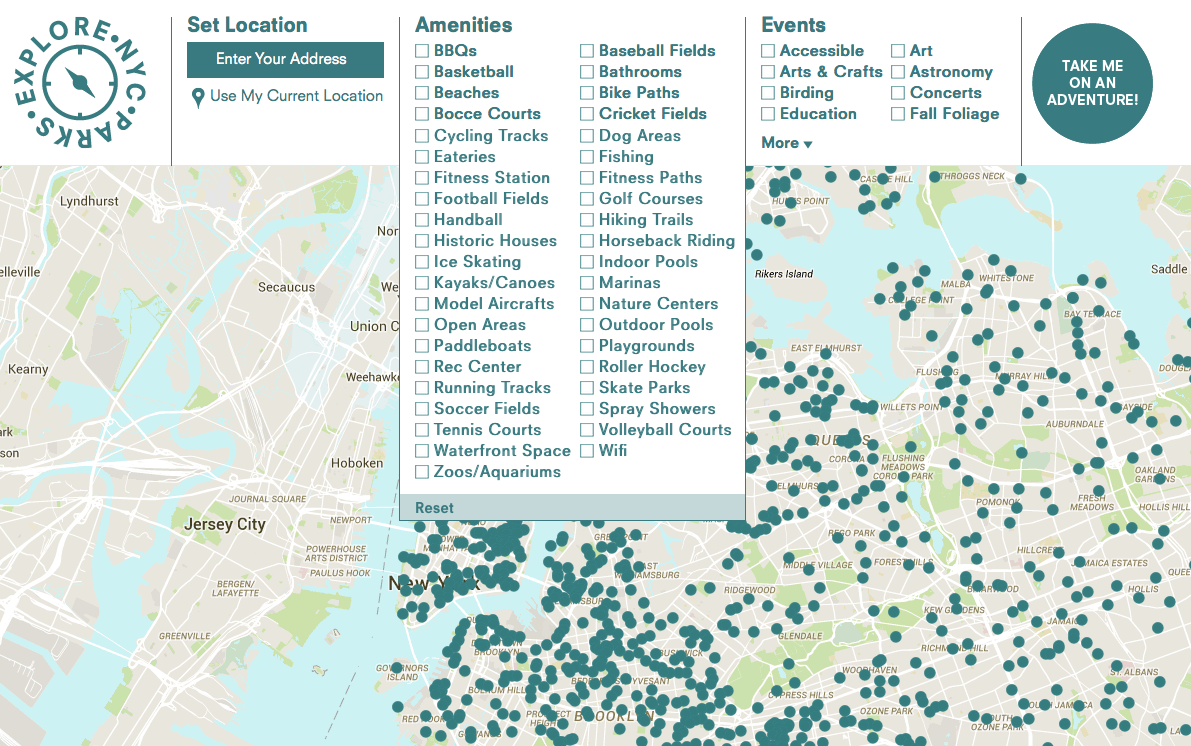

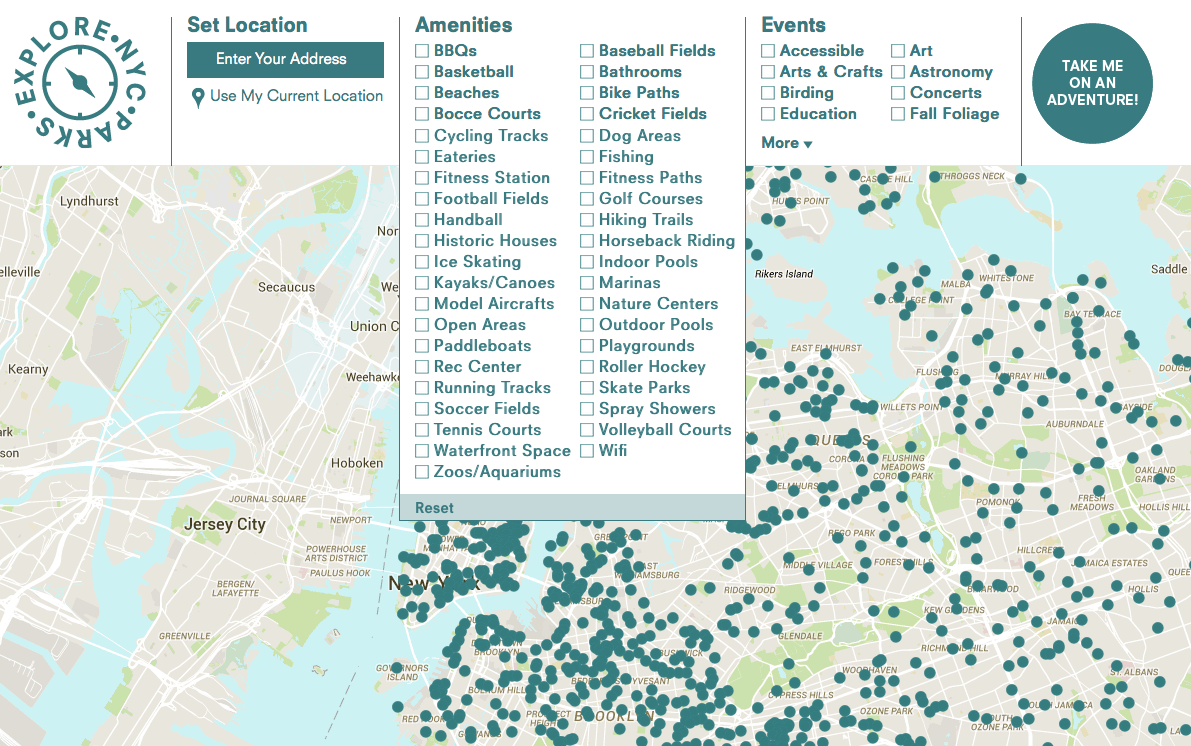

Sometimes simplicity is the best answer, as we can see by Explore NYC Parks, an app to find your nearest parks and filter information by type of facilities: barbecues, beach, cycle path, baseball field, canoeing, etc.

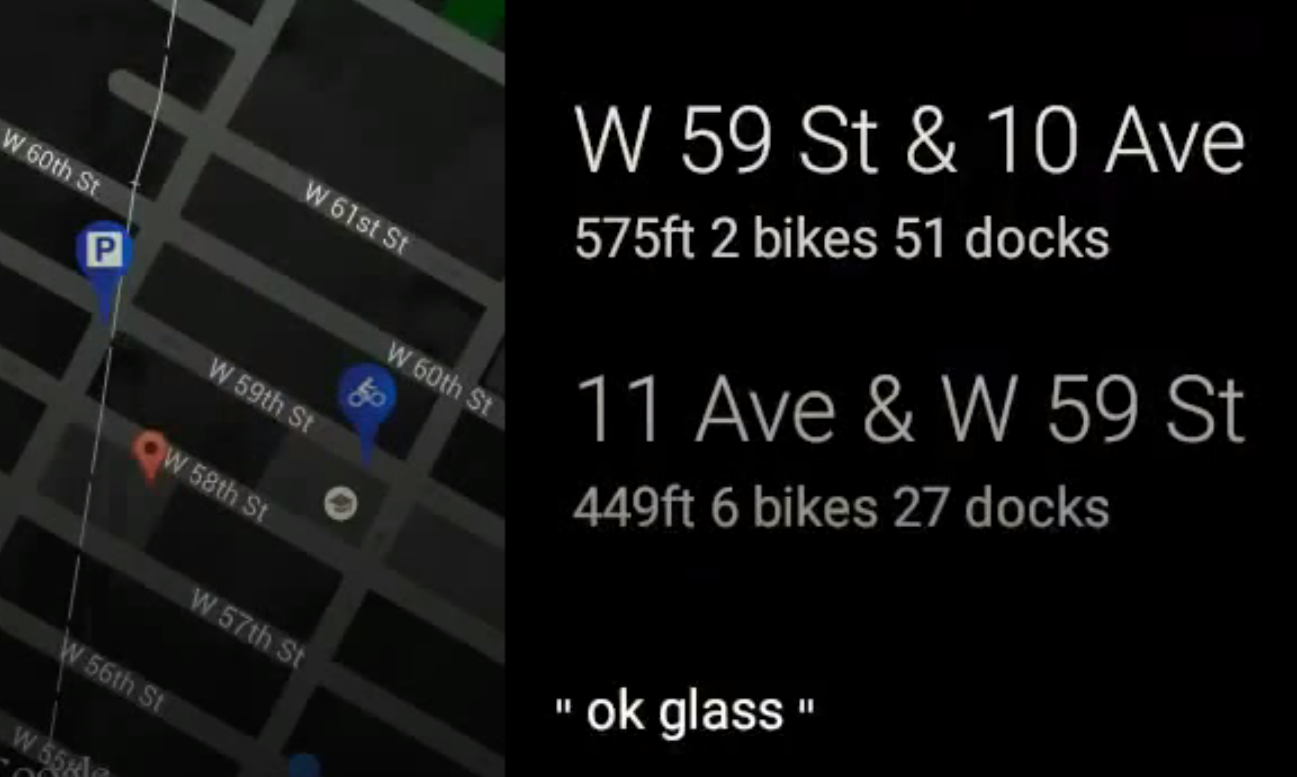

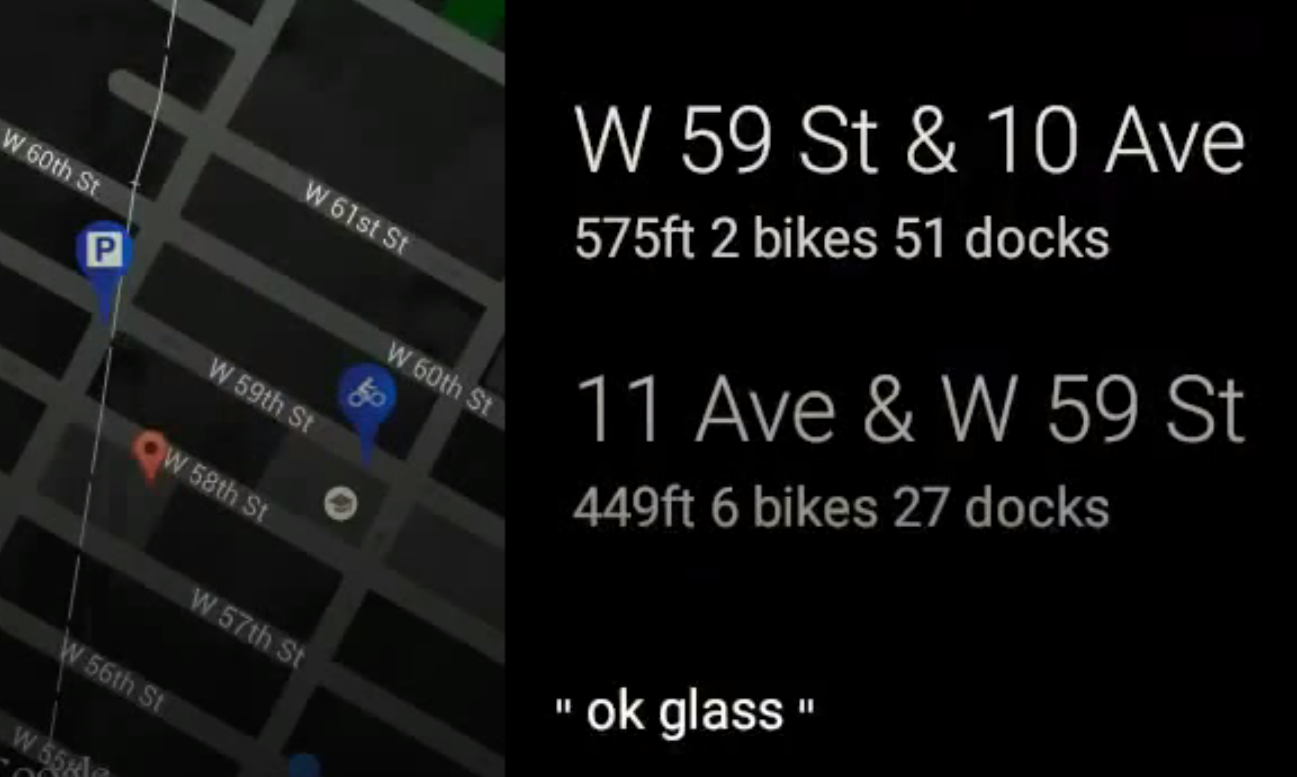

CityRide shows cycle routes, and lets users of public bikes know where they can collect or park their bikes using Google Glass.

It is really important that these projects last. For example, the Brooklyn borough (under President Eric Adams) has begun a pilot program from Heat Seek NYC, an app that will be applied to 10 borough buildings to measure their heat levels. A winner of BigApps 2014, this hardware measures heat inside buildings, gathers this information on a platform and makes it accessible to public authorities. The aim is to allow tenants to optimize their energy consumption in buildings where there is excess heat, and to put pressure on owners of houses with temperature-related problems to solve them. Adams will install one of these systems in his own house.

Promo Video (High Res) from Heat Seek on Vimeo.

During the 2014 edition of this competition, the mentoring system seems to have been improved. Each mentor was only asked to give 15 hours of his/her time in three months to: direct or guide programmers through prototype creation, liaise between participating teams and potential partners for concept and market testing, practice pitch with possible investors, and help to publicize the applications. In exchange, mentors had access to creative talent and were recognized for their contribution to the development of technology solutions to major city challenges. Truly noteworthy learning.